By Dr. Mike Ruyle, Marzano Resources; Dr. Mario Acosta, Marzano Resources; Nancy Weinstein, MindPrint Learning

This blog was originally published on Marzano Resources.

What can schools do?

Mental and neurological health has become one of the most pressing human issues worldwide, and its impact on children and adolescents has been especially profound. The COVID-19 pandemic, in particular, significantly disrupted school cultures, and the overall instability in all segments of society has exacerbated stress and anxiety among students, teachers, and principals (Mazrekaj, D., & De Witte, K. 2023; d’Orville H. 2020).

In our work with schools since the spring of 2020, we have encountered deep frustration among educators at the seemingly relentless onslaught of issues, including increases in negative student behaviors, chronic absenteeism, and widespread declines in student engagement and academic achievement. Faculty exhaustion and staff shortages have stretched teachers thin, leaving many with less of the patience needed to manage student behaviors. This has made school environments more tense than at any time in recent memory. In fact, roughly 70 percent of educators state that the rise in student behavior concerns continues to worsen (Gonzalez, A., Vandenbosch, L., & Rousseau, A., 2023; Prothero, 2023). The struggle is deep and far-reaching.

There has been a tendency to attribute student academic and behavior challenges to home or societal factors that are beyond the purview of schools. Although it can be easy to blame elements such as social instability, general lack of motivation, and heightened levels of depression and anxiety, mounting evidence from the developmental and learning sciences suggests that primary reasons students are struggling in classrooms entail difficulties with executive functions, memory, and retention of learning.

We strongly assert that most problem behaviors are simply a result of young people being unable to effectively manage the environments in which they currently operate.

For example, recent studies highlight significant impacts of smartphone and social media use on neurological functions of students. Neuroimaging research indicates that excessive smartphone use can lead to structural changes in the brain, particularly in regions associated with emotional regulation and cognitive control, resulting in increased impulsivity and reduced emotional stability (Montag & Becker, 2022). This aligns with findings on students, where high social media use is linked to decreased attention spans and impaired working memory, which can detract from overall cognitive performance (Cain & Mitroff, 2022). The mental health of students is also a concern, with social media contributing to heightened risks of depression and anxiety, exacerbated by constant exposure to idealized images and social comparisons (HHS, 2023).

In addition, a soon-to-be released large-scale study (n = 47,687) focused on neurological changes in students following the COVID-19 pandemic and uncovered substantial decreases in most cognitive skills, with the largest declines seen in memory and flexible thinking. This phenomenon differentially impacts the more vulnerable in that the greatest declines were seen in the youngest learners as well as lower-income students. The study’s authors powerfully suggest that declines in cognitive skills such as complex reasoning, memory, and executive functions directly contribute to declines in achievement and increases in negative behavior. They may also be the predominant cause of many of the challenges facing schools today (Tsai, N., Weinstein, N. in prep, 2024).

Interestingly, many of these cognitive challenges are not limited to students. This study also indicated that although educators typically exhibit above-average cognitive skills, especially in complex reasoning, they also display moderate declines in adult cognition that are consistent with trends in students. These findings are vital to understanding the current educational reality because weaker executive functions in students combined with weaker executive functions in adults can help explain challenges in classroom management across all ages and demographic groups (Tsai, N., Weinstein, N. in prep, 2024).

Recommendations

Given what is known about brain malleability and the benefits of early intervention for academic achievement, we suggest a two-pronged approach, entailing both short-term interventions as well as long-term objectives to address a new vision for schooling. These needs are most critical for elementary-age and lower-income students, which is where the largest declines in memory were seen. Fortunately, both executive functions and memory skills can be supported and enhanced in the classroom through well-established and relatively simple strategies.

Short term: focused instructional effectiveness

Some immediate relief can be realized in schools by improved teacher commitment to implementing some vital instructional strategies within the classroom environment that can:

- Enhance memory to ensure retention of fundamental knowledge

- Strengthen executive functions

First, implementing proficiency scales into daily classroom instruction can be a powerful strategy to empower students to monitor their own progress toward mastery of critical skills. It can also help students to tap into their prior knowledge, which is an effective and culturally affirming way to enhance verbal and visual memory as well as attention. The effective use of proficiency scales—which entails increasing teacher effectiveness around direct instruction lessons by focusing on chunking content, processing content, and recording and representing content—are vital to providing students with the basic knowledge necessary to deepen their skills in subsequent lessons.

Second, teachers must provide powerful instruction focused on literacy skills such as enhancing comprehension and increasing academic vocabulary knowledge. Since automaticity is fundamental to reading fluency and foundational math knowledge, ensuring a solid grasp of basic literacy skills is vital to any subsequent success. Every teacher at every level of education should be adept at helping students master critical vocabulary as well as basic literacy skills to increase student access to high-level knowledge and standards.

Also, establishing tech-free zones can help both teachers and students focus on face-to-face interactions and reduce the cognitive load associated with constant smartphone use (HHS, 2023). Additionally, integrating digital literacy programs into the curriculum can educate students about responsible online behavior and the potential psychological impacts of excessive social media use (Cain & Mitroff, 2022). Educators themselves should model balanced technology use, showing students effective ways to manage screen time and prioritize mental well-being. By fostering a school culture that emphasizes mindful technology use and provides support for mental health, educators can help students navigate the digital world more safely and effectively (Montag & Becker, 2022).

Finally, incorporating simple, daily mindfulness practices in classrooms can help facilitate healing, build neurological resilience, and enhance flexible thinking skills. Mindfulness can also help reduce stress and improve cognitive functioning for both students and teachers. Simple techniques such as deep breathing, meditation, using music, and employing gratitude exercises can foster a calm and focused learning environment and can also strengthen parts of the brain that are fundamental to learning (Lazar, et al, 2005). Implementing rituals and traditions that celebrate achievements, both big and small, can boost morale and foster a sense of personal growth as well as belonging that can also enhance cognitive resilience and flexible thinking (Caballero et al., 2019; Deal & Peterson, 2016).

Many of these strategies are not only beneficial for students but also help alleviate faculty exhaustion and improve classroom management, contributing to a more stable and effective learning environment.

Long term: Cultural shift to a more humanized model of schooling

School culture plays a crucial role in bringing the transformations recommended in this article to fruition. A school’s cultural alignment with these recommendations is essential for implementing the short-term interventions and long-term objectives suggested to address cognitive and behavioral challenges exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Research underscores the importance of organizational culture in achieving success. For instance, research by Gruenert and Whitaker (2015) highlights that a supportive and inclusive school culture fosters a sense of belonging and community, which is vital for cognitive health and student engagement. Additionally, research indicates that a strong school culture can enhance employee satisfaction, productivity, and overall performance (Chatman & Gino, 2014).

As such we recommend a long-term vision that entails schools adapting and expanding their cultures by fostering environments that support mastery-based educational principles as well as mental health and cognitive recovery so that they can more effectively engage in trauma and culturally responsive practices to heal traumatized brains and build resilience in all brains.

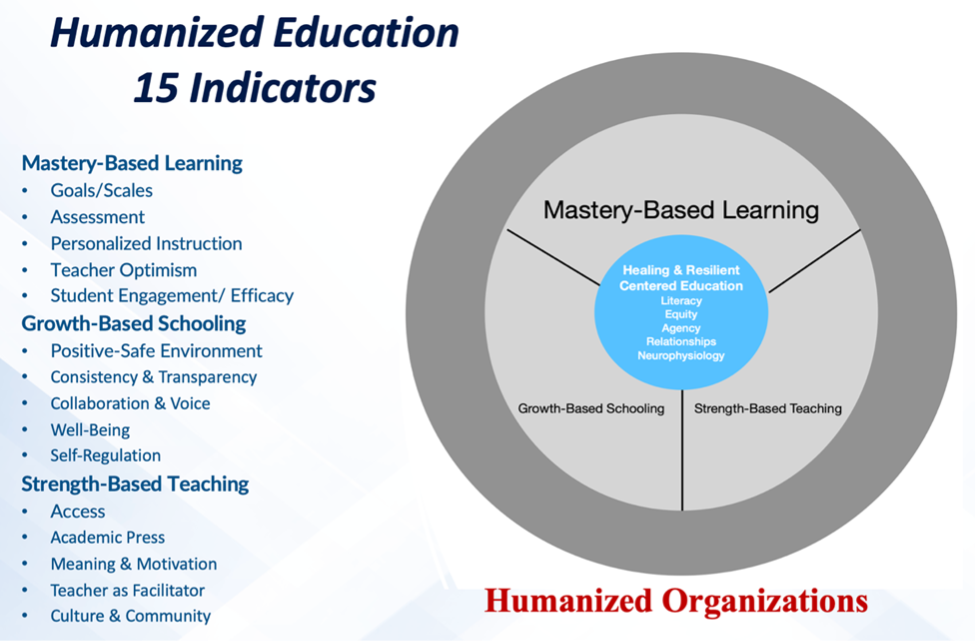

A positive school culture is the foundation upon which successful educational experiences are built. Communicating a clear and compelling vision that emphasizes the importance of academic excellence, equity, and holistic development is essential for guiding behaviors and decision making (Deal & Peterson, 2016). The long-term vision must focus on a clear integrated framework for school that embraces mastery-based learning components along with critical elements of growth-based schooling and strength-based teaching, as presented in the visual below.

Summary

A new normal is upon us. Thus, an evolved model of schooling that effectively addresses the vast complexity of the learning process—one that is more humanized than standardized—is urgently needed.

The most critical key to addressing academic and behavioral challenges should start with acknowledging the potential mental and psychological issues that are at the root of the problem. This is particularly important given the significant cognitive declines observed in students and educators post-pandemic (Tsai & Weinstein, 2024). With a laser focus on cultivating environments that emphasize mastery-based principles, literacy skills, mindfulness, and executive function development, schools can help mitigate these declines and promote academic and social success.

Schools with a strong culture that aligns with their strategic goals tend to outperform those that do not (Denison et al., 2014). By consciously making vital educational adjustments to address cognitive functions and neurological health, improvements in student self-regulation, engagement, and ultimately, academic and social success should follow. And, by fostering a positive school culture that supports the recommended transformations, schools can create an environment where both students and educators thrive, ultimately leading to improved academic achievement and overall well-being.

References

Caballero, C., Scherer, E., West, M.R., Mrazek, M.D., Gabrieli, C.F., & Gabrieli, J.D. (2019). Greater mindfulness is associated with better academic achievement in middle school. Mind Brain Education, 13, 157-166.

Cain, M. S., & Mitroff, S. R. (2022). Cognitive functioning and social media: Has technology changed us? Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563220303389.

Casedas, L., Pirruccio, V., Vadilllo, M.A., & Lupianez, J. (2020). Does mindfulness meditation training enhance executive control? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in adults. Mindfulness, 11, 411-424.

Chatman, J. A., & Gino, F. (2014). The role of organizational culture in the success of an organization. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 479-509.

d’Orville H. (2020). COVID-19 causes unprecedented educational disruption: Is there a road towards a new normal? Prospects (Paris). Published online 2020 Jun 3. doi: 10.1007/s11125-020-09475-0

Deal, T. E., & Peterson, K. D. (2016). Shaping school culture: Pitfalls, paradoxes, and promises. John Wiley & Sons.

Denison, D. R., Nieminen, L., & Kotrba, L. (2014). Diagnosing organizational cultures: A conceptual and empirical review of culture effectiveness surveys. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(1), 145-161.

Gonzalez, A., Vandenbosch, L., & Rousseau, A. (2023). A panel study of the relationships between social media interactions and adolescents’ pro-environmental cognitions and behaviors. Environment and Behavior, 55(6-7), 399-432 https://doi.org/10.1177/00139165231194331

Gruenert, S., & Whitaker, T. (2015). School culture rewired: How to define, assess, and transform it. ASCD.

HHS. (2023). Surgeon general issues new advisory about effects social media use has on youth mental health. Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov.

Lazar, S. W., Kerr, C. E., Wasserman, R. H., Gray, J. R., Greve, D. N., Treadway, M. T. (2005). Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. Neuroreport, 16(17), 1893–1897.

Mazrekaj, D., & De Witte, K. (2023). The impact of school closures on learning and mental health of children: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916231181108

Montag, C., & Becker, B. (2022). Neuroimaging the effects of smartphone (over-)use on brain function. Psycho Radiology. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/psyrad/article/doi/10.1093/psyrad/kkad001/7022348.

Prothero, A. (2023). What it’s like teaching through a youth mental health crisis. Education Week. May 15, 2023. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/what-its-like-teaching-through-a-youth-mental-health-crisis/2023/05

Tsai, N. Jaeggi, S., Eccles, J., Atherton, O., & Robbins, R. (2020). Predicting late adolescent anxiety from early adolescent environmental stress exposure: Cognitive control as mediator. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1838.

Tsai, N., Weinstein, N. (pending 2024). Age and income related changes in cognitive functions in school aged students following the COVID-19 pandemic. MindPrint Learning. Princeton, New Jersey.